A Room Covered with Six Tatami Mats 2019 1 22 Sunshine Lee's Culture Essay written in Poetry A Room Covered with Six Tatami Mats It is said that the room Poet Dongju Yun used while studying in Japan in the 1940s needed only(?) six tatami mats. The room that I used in the same university 70 years later was the same size. According to the information on the dormitory provided by Doshisha University, I had to share a kitchen with other students if I were to stay in the school dorms,. So I made an early visit to Kyoto to look for my own place to stay. My budget for lodging was several times larger than boarding expenses for the school dorm, but perhaps it wouldn’t be enough. I looked at 6 places in a day but they were all similar; I felt sorry for the person who was helping me, and said I would rent the last place we looked at but then immediately regretted it. The last place was too small. There was a tiny bathroom, a kitchen, a restroom and an attic, but the size of the room itself looked to only be about 10m2. Just as in Dongju Yun’s poem, I was living in a room of only six tatami mats. I wanted to change my decision, but the next month I would return to Kyoto and start the semester. So, I didn’t have the time or energy to change lodging. I left trivial but essential things like spoons, dishes, knives, scissors, pencils, scotch tapes at my home in Seoul and just brought books, notebook, a few pieces of clothes and a thick blanket – I hadn’t thought to pack like a long-term visitors should, and instead packed like a tourist. I thought that it would take only a few days to buy everything I needed. But it ended up taking two months as things that I needed kept popping up. And, one thing that caught my eye were flowers, which I bought immediately. I did so because it felt stuffy in my room. It would have been fine if the window wall had an open view, but a low building was blocking the view. I kept buying flowers to breathe – I bought about a dozen in total and arranged them by color on the floor outside the window. It was very different from when I lived in the U.S. The student who was helping me would scold me for buying flower after flower when what I really needed was a rice cooker. When I came back at night, the first thing I did was open the window and water the flower. Petals and the dainty leaves welcomed me. When I was forced to return to Korea after graduation, I gave most of my household goods like blankets and chairs to my friends, and it was a shame that I couldn’t take with me to Korea those pretty flower pots that had comforted me. It didn’t take long for me to realize that studying late in life was not as simple or easy as I thought it would be. First of all, a certain level of Japanese was a must if I wanted to study in Japan, and it was hard to keep up with 20 courses with my elementary level of Japanese. After the Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011, my two collections of poems published in both Korea and Japan became a huge issue, and I was invited to give a speech in Japanese in Japan several times. Looking back, I realized that I had never studied Japan. I felt somehow guilty because of this, and I thought of studying Japan, even though it had been 40 years since I studied at graduate school in the US. It took a year and several applications. I was only focused on applying; I wasn’t properly prepared for the workload after getting in. My imprudent decision was irreversible, so I decided to finish studies fast at least. To do that, I had to study all day. It was past 10 p.m. after the school library closed and I took my backpack to leave. I hoped to do well in Japan—giving speeches and lectures and doing exchanges. I also hoped to be able to keep up with studies and complete the whole course. Yet, after actually trying it, I realized that I had to choose one or the other if I wanted to graduate –in fact, it would be a miracle if I could even do that. I had already said farewell in Korea before coming here – if I didn’t want to fail, I had to give up on my first ambition, and devote all my energy and time to the second ambition – to graduate by passing all my exams and going through coursework in 20 classes. Studying was stressful, but the students were kind, and professors were too kind and too humble, not authoritative. It really differed from when I studied in Korea and the USA. The staff working in school cafeteria and stores frequently bowed to students and were very modest. That might be ordinary life to them, but I was taken by surprise every time. There is a chapel built of brick by Niijima Jō, the founder of Doshisha University, in front of the library. And right next to the chapel are poetry monuments of Dongju Yun and Ji-yong Jeong, Korean poets. It was interesting that there were not one but two poetry monuments of Koreans when many students came to study in Doshisha from many countries over the last 150 years. Granted, Dongju Yun has received a lot of attention with the movie and TV programs about him, but he was generally unknown throughout his short life of 27 years, and suffered a lot. He wrote poems in Korean which led to his arrest for “instigating independence movement”, and he was imprisoned in a Fukuoka prison, and died there just before liberation of Korea. In this beautiful campus without a speck of dust, only the neighborhood of the two monuments was not cleaned or touched. So almost every day I wiped the front side of the monument and threw out the litter. I also read the poem Dongju Yun wrote in agony in his room covered with six tatami mats. I wanted to understand his feelings. It’s not the Japanese colonial period now, what on earth am I doing here, staying up all night with a notebook open in this tiny room? This is the question I asked of myself every night. A long time ago, when I came to Kyoto to attend an event for my mom held by the Japanese government, Kyoto felt like my long-lost hometown. At least that was how I felt when I was staying in Kyoto for a few days. Now that I was staying long-term, and had an enormous amount of homework, I felt like this place was a foreign land even though people were very nice to me. I became entangled in the affairs that I left behind in Korea. Nostalgic feelings overpowered me. After taking a shower, I walked along river Kamogawa in the dark night. The poem engraved in the poetry monument for Ji-yong Jeong, whom Dongju Yun looked up to as his teacher, was “Kamogawa.” Singing about plaintive and mournful feelings in a foreign land. After it became known that there was a poetry monument for Dongju Yun, tourists from Korea started visiting Doshisha University which required no admission, to look at the poetry monument and read “Kamogawa”, engraved in the poetry monument for Ji-yong Jeong located right next to the poetry monument for Dongju Yun. In the poem there is a mother, there is someone chewing on a orange peel, there is the scent of watermelon, the wind blowing over the water, and the narrator’s lover—as well as Kamogawa and its 4000m. If you stayed in Kyoto for just a few days, you would never understand how this Korean poet had felt. Even now, whenever I am in Kyoto, I go to the Demachi neighborhood, room number 103 in the 3-floor building, and the door I used to use. I think of the moments when I would come back late from the university library, study and write late into the night on desk and the floor, change the arrangement of flower pots, prepare brown rice for boiling, treating my friends with dinner spread on the floor, and the moments when I would pray because I was sad and lonely. My body has left the place, but I face and observe the memories and its aura that are still staying there. A Poem I’ve Written Easily

A night rain whispers outside thewindow.

The floor of my room in a foreign land

is covered with six tatami mats

Knowing that being a poet is a solemn duty

Let me try to jot down a poetic line

The smell of my parents' sweat and affection

fills the envelope containing my tuition

With a notebook under my arm

I head for an old professor's lecture

I come to think of my childhood friends

First one, then another, they're all gone

What do I hope for as I sink alone?

Life is so hard,

and yet I've all too easily written a poem

It’s shameful

The floor of my room in a foreign land

is covered with six tatami mats

A night rain whispers outside the window

Turning the lamp on,

the darkness goes away

I, as if a man on the last day,

await the morning

to break forth like a new age

Offering myself my small hand,

I propose the first handshake

in tears and comfort.

PC, desk and memos on the wall of my room covered with six tatami mats, 2016

A closet and a mirror

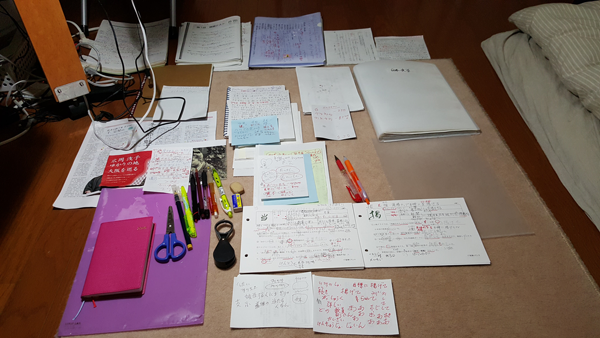

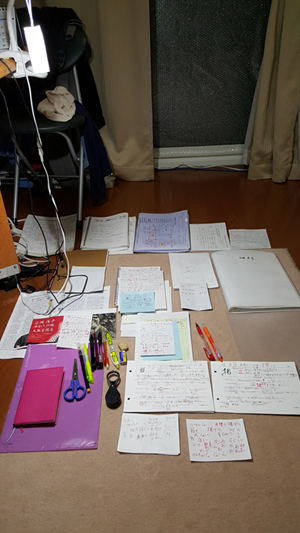

A note and memo spread after 10 p.m. when the library closes

Homework on the floor of the room covered with 6 tatami mats, 2016  he flower shop from which I kept buying flower, riverside of Kamogawa, March 2018 he flower shop from which I kept buying flower, riverside of Kamogawa, March 2018

Café Bon Bon overlooking Kamogawa river where I used to study eating French toast in the early period?

Dinner I treated to friends, with dish spread on the floor beneath the desk |